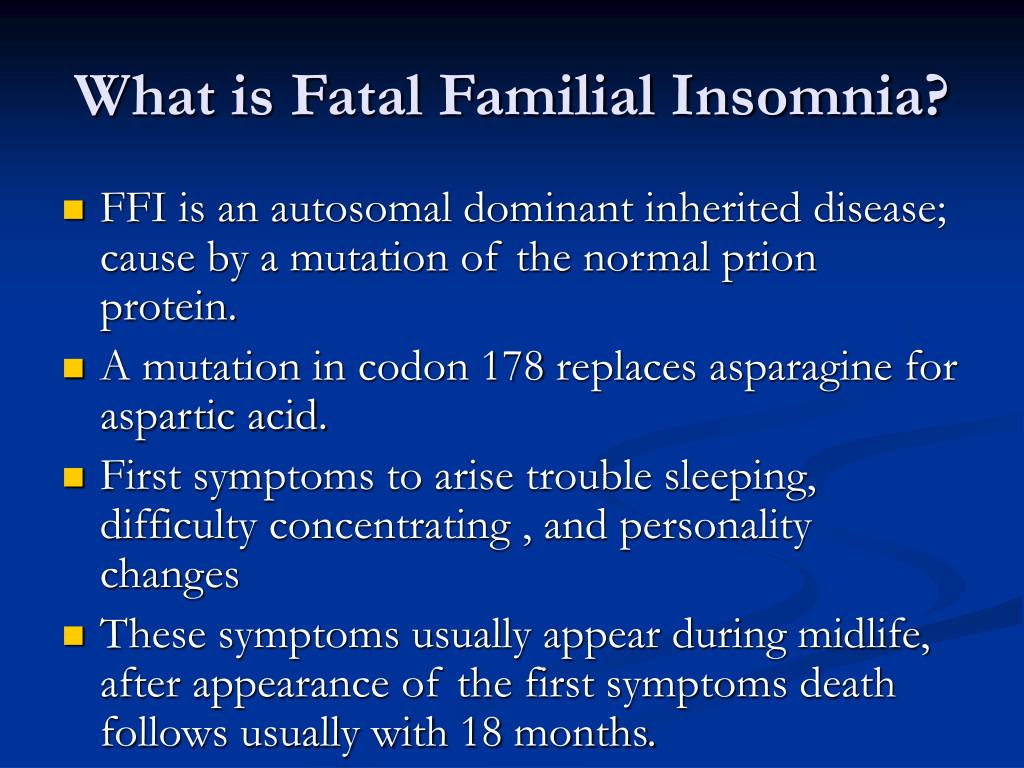

By the time he had been admitted to the hospital, about 130 days had passed with minimal sleep. In the disease, sleep becomes progressively disrupted until patients exhibit little to no sleep. This helped doctors to realize that he was suffering from a disease that had only been recognized within the previous decade, called fatal familial insomnia (now often called fatal insomnia because not all cases seem to be hereditary). They diagnosed him with multiple sclerosis, despite the fact that he didn't really have the symptom profile of someone with the disease.īut doctors soon recognized that something was very unusual about Corke's "sleep." Even though Corke would often close his eyes and appear to be sleeping, measurements of his brain activity found that his brain never did actually fall asleep. His decline had been rapid and pervasive.Īt first, doctors could not figure out was wrong with Corke. He had become completely dependent on his family to help him perform even the simplest tasks like showering and getting dressed. At that point, Corke was unable to communicate. Sometimes these episodes involved hallucinations.Īfter Christmas, he was admitted to the hospital. He began to display signs of dementia and there were times when he appeared to lose touch with reality. He developed problems with balance and had trouble walking.

Within a few months, Corke's lack of sleep was causing obvious physical and mental deterioration. Nor was he suffering from the common problem of waking up frequently over the course of the night. It wasn't just taking him longer to fall asleep than normal. He had recently turned 40, and seemed to be in good health, but it was soon very obvious that he was suffering from more than just your run-of-the-mill insomnia. Corke was enjoying the summer break from his position as a music teacher in a Chicago high school when he started to develop sleeping problems.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)